The Ancient Aprons

The Apron is not a modern invention; in fact it is the most ancient of all garments. In the 3rd Chapter of genesis these words are written: “and the eyes of them both were opened, and they knew they were naked, and they sewed fig leaves together, and made themselves aprons.”

Aprons have been used in religious rites since time immemorial especially when delivering burnt offerings and blood sacrifices of various animals to the altars of ancient gods. On monuments and wall paintings in Ancient Egypt a garment, which can best be described as a triangular apron with the point upward, is depicted, in circumstances indicating that the wearer is taking part in some kind of ceremony of initiation. In connection with this fact, it is interesting to note that in Egypt it was customary to bestow a ‘collar of office’ on those whom the Pharaoh wished to honour. Such collars were circular in shape and on many occasions the Pharaoh himself is depicted wearing one in addition to his crook and flail as a symbol of his high office.

In China, some of the ancient figures of the gods wear semi-circular aprons, very similar to some of Scottish aprons, and some of these gods are often depicted making the sign of a well known ‘High Degree’.

In Central America the ancient gods are constantly sculpted wearing aprons. Tepoxtecatl, the preserver, for example, is depicted wearing an apron with a triangular flap, and on his head he is wearing a conical cap on which can clearly be seen an embroidered skull and crossbones, finally he holds in his right hand a hammer or gavel.

Examples of ancient gods wearing aprons can be found spread over the four quarters of the globe. It will be no surprise therefore that priests wore similar aprons as a sign of their allegiance to the ‘gods’ and as a badge of their authority. The earliest ceremonial apron known to have been used in Palestine was introduced by the Canaan Priest-King Melchizedek. Dated to around 2200 BC, the Melchizedek Priesthood began to make its ceremonial aprons out of white lambskin. White lambskin was eventually adopted by the Freemasons who have used it for their aprons ever since. Therefore when the Senior Warden exhorts the candidate that the apron that has been invested with is ‘more ancient than the Golden Fleece or Roman Eagle; more honourable than the Star or Garter, or any other Order in existence’ he is not simply exaggerating to make a point, he may actually be stating an actual truth.

In any case, there is a legend describing why Freemasons use lambskin aprons and not that of any other animal and this legend can be traced back to the building of King Solomon’s temple:

“When the construction of King Solomon’s Temple was commenced, workmen were selected to carry out the different trades. Hiram, the widow’s son, proclaimed that before entering upon the undertaking the aid of God should first be invoked, and as the Temple was to be God’s Holy House and erected to Him, each workman having a part in its construction should offer a sacrifice to God on the Altar of Burnt Offering. The Lamb had in all ages been deemed an Emblem of Innocence and was offered as a sacrifice. With the exception of the skin, the whole of the lamb was consumed. The skins were properly prepared and Hiram caused aprons to be made of them. One apron from the skin of each lamb sacrificed, one apron for each mason under him.”

Finally the Templar Rule forbade any personal decoration except sheepskin, and further required that the Templar wear a sheepskin girdle about his waist at all times as a reminder of his vow of chastity, a context within which purity and innocence are vital.

The old Masonic Apron

As we have seen aprons have throughout the ages possessed a religious and symbolic meaning, a fact that is well applied to our own present

apron as I will shortly demonstrate. However, there is little doubt that the Masonic apron evolved from those worn by operative masons to protect their clothes from becoming soiled. In medieval times all masons, whether freemasons or Guild Masons, used aprons when at work, and the former also wore white leather gloves to protect their hands from the lime.

This type of apron used by the speculatives had changed very little in the middle of the 18th century from those used by the operative counterparts. These aprons were long, coming down to below the knees, with a flap or bib to protect the chest.

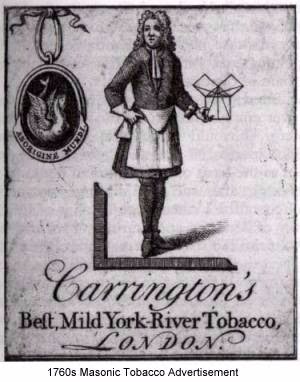

It was the speculative masons who at some point in the 1750’s began to decorate their aprons with designs, usually painted by the owner’s own hand.

A number of these examples can still be seen in the Museum and Library of Grand Lodge, but we must remember that at this time no definite scheme existed and each brother was free to adorn his own apron as he saw fit, usually including all the symbols of all the various degrees he had attained. Therefore, many of these designs included symbolism of such degrees such as the Mark, Chapter and Ark Mariner in addition to those of the Craft. In due course however, certain designs became more popular and more standardised. The two pillars with the letters that represented them, and often the names were even given in full became an accepted model for most aprons. To this central motif were added various other emblems such as squares, ladders and so forth which can be found in the 1st degree Tracing Board and Masonic Certificates issued to all Master Masons advanced to the 3rd degree.

The Modern Masonic Apron

The Union of the Grand Lodge of England between the Ancient and Modern branches of English Freemasonry in 1813 brought into many effect many changes in dress and ritual which still prevail to this day. The deviation from certain aspects of the ritual is in my opinion regrettable but outside the boundary of this lecture. However, in respect to the Masonic apron it was felt necessary to have these standardised and the resulting effort are the aprons we have in use today. Nevertheless, even though we may assume that today’s aprons are but a shadow in respect to the decorative beauty of 18th century aprons they still contain much Masonic symbolism and inner meaning which I will now proceed to explain. However, before I do so, I must point out that the Masonic apron I am going to refer to is strictly that as worn by Masons of the English Constitution and not to those of the other constitutions. For example the Dutch wear an apron bordered with black and with a skull and crossbones on the flap. Scottish lodges each have their individual right to choose the design, colour and shape of their aprons; some employ a tartan, while many others have a circular rather than a triangular flap. This is the reason why all four Scottish lodges dress in different regalia whilst all English lodges have adopted the same model. Irish aprons appear to be a bizarre attempt at standardization with tinges of individualisation in the apron borders and embroidery.

To the eye Irish aprons may well appear the same, but I have yet to see two which are exactly the same. Returning to the English apron, many Brethren still believe that the present apron was the result of an accident and that no deliberate attempt at symbolism was envisaged. However, by the end of this explanation of the hidden meanings and symbolism of our present apron you too will I am sure come to the conclusion that those who designed it had a much deeper knowledge of symbolism than the apparently ‘simple’ Master Mason apron leads us to believe.

Firstly, let us consider the colour of the Master Mason’s apron, which is that of Cambridge University, and likewise that used by Parliament when fighting King Charles, has a much deeper significance than is generally known. It is closely related to the colour of the Virgin Mary, which in itself has been brought forward from Isis, Astarte and other Mother Goddesses of the ancient world, whose symbol was always the moon and seven stars.

You may have noticed that many statues of the Virgin Mary show her wearing a diadem or crown of seven stars on her head and her cloak is light blue, the colour of our Masonic apron. In contrast, the aprons of District and Grand Lodge Officers have Garter Blue, often connected with certain Orders of Knighthood, but also this blue is the colour of Oxford University, and the colour associated with the Royalist cause during the Civil War. Thus the two aprons in use amongst Brethren of the English craft employ the colours of the two great Universities of England. The dark blue colour therefore can be said to represent the rulers in the Craft, and represent the masculine element. Light blue, on the other hand, represents the feminine or passive aspect, and is most appropriate for the ordinary Master Mason, whose duty it is to obey and not to command. The other significant emblems representative of the female aspect are the three rosettes, symbol of the rose itself, itself a well known substitute for the Virgin Mary herself as the Mystic Rose. The three rosettes on a Master Mason’s apron are arranged so as to form a triangle with the point upwards, interpenetrating the triangle formed by the flap on the apron, alluding to the square and compass.

The two rosettes on a Fellow Crafts apron stress the dual nature of man and have a clear reference to the two Pillars. The two rosettes also point out that the Fellow Craft has not yet a complete Freemason as it requires a third rosette to form a triangle. The Fellow Craft’s apron thus represents the wearer’s status as being superior to an Entered Apprentice but inferior to that which in due time he will attain and which the third rosette will invariably complete in the form of the interlaced square and compass.

As the Master Mason advances and becomes Master of his Lodge, the rosettes of his apron give way to three Tau or levels as they are generally called. The Tau is the symbol of the Creator and also the symbol of the Royal Arch to which all Masters had to be exalted to that supreme degree before he could accept the Chair in a Craft lodge.

Another important feature of the apron was the tassels which originally represented the ends of the string used to tie the apron round the waist. It was only a matter of time before these strings were decorated with tassels and even today certain aprons, such as those worn by members of the Royal Order of Scotland use this type of string with ornamental tassels which when properly tied together at the front cause the two tassels to stick out from under the flap.

Craft aprons have now replaced the string or cord with a band attached to a hook and eye and so tassels have been replaced by two strips of ribbon on which are attached seven chains. The seven chains themselves are full of symbolic meaning and represent various Masonic allegories such as the 7 liberal Arts and Sciences, the number of Masons required to make a perfect lodge, the number of years it took king Solomon to build the temple, etc. The two ribbons and chains are also representative of the old pillars that used to adorn the apron before these were replaced with the existing form.

Finally we arrive at the band with the hook and eye attachment that perhaps nobody may be aware is also full of symbolic significance. It is no accident that the snake was selected for this purpose. The snake is the traditional symbol of evil, but it is also associated with wisdom. Thus the serpent in our apron denotes that we are encircled by Holy wisdom. You will also notice that the serpent is biting its own tail, thus forming a circle which has always been regarded as the emblem of eternity, and more especially the Eternal Wisdom of God.

As you can see Brethren the apron is not just a piece of regalia we wear simply to distinguish the different grades of Freemasons or even for cosmetic effect and pomp. It is a vital part of our ritual and why any Mason in a lodge who is not wearing his Masonic apron is considered quite rightly to be improperly dressed. Thus it will be seen that our apron is a very honourable garment, one that we should treasure. It is an apron made of lambskin, pure white, without fault or stain – the colour of the Soul as mortal man sees it. It is ours and it now depends upon each of us to keep it without blemish – to keep it as a mirror of our soul that we may stand the final test when we reach into Life Eternal – which is just beyond.

WBro. Keith Sheriff

Appendix

Belgium.

– The Grand Lodge Aprons are of light blue silk, embroidered with gold fringe,

without tassels. The collars are embroidered with gold with the jewels of

office, and with acacia and other emblems.

Egypt.

– The Grand Orient uses the same clothing as the Grand Lodge of England, but the

colours are thistle and sea green. The rank of wearer is denoted by the number

of stars on his collar.

France.

– The Grand Orient has aprons very elaborately embroidered or painted and edged

with crimson or blue. In the third degree, blue embroidered sashes are used

lined with black.

Greece.

– In recent years the clothing has become exactly identical with that worn in

England, although formerly silk and satin aprons painted and embroidered with

crimson were worn.

Germany.

– Aprons varied greatly in size and shape, from square to the shape of a shield.

Some bear rosettes and others the level. There is no uniformity and German

Lodges had jewels apparently according to the taste of each.

Holland.

– Each Lodge selects its own colours for aprons and the ribbons to which the

jewels are attached. Individuals may use embroidery, fringes, etc., according to

their own fancy.

Hungary.

– The members of Grand Lodge wear collars of light blue silk with a narrow

edging of red, white and green-their national colours-from which are suspended

five pointed stars. The Grand Lodge Officers wear collars of orange colour edged

with green and lines with white silk. They are embroidered with the acacia and

the emblems of office. The aprons have a blue edging with three rosettes for a

Master Mason.

Italy.

– The Entered Apprentice apron is plain white silk. The Fellow craft is edged

and lined with a square printed in the centre. The Master Mason wears an apron

lined and edged with crimson, bearing the square and compasses. He also wears a

sash of green silk, edged with red, embroidered with gold and lined with black

on which are embroidered the emblems of mortality in silver. It must be

remembered, however, that Freemasonry for some time past has been suppressed in

Italy, the reason being that it intermeddled in national politics.

Iceland.

– Plain white aprons, edged with blue, bearing the number of the lodge. At the

Annual Communication lambskins are worn with a narrow silver braid in the centre

of the ribbon. In former days, the Worshipful Master always wore a red cloak and

silk hat.

Portugal.

– The apron of the Grand Lodge Officers are of white satin, edged with blue and

gold and with three rosettes. The collar is made of blue silk with the acacia

embroidered in gold.

Spain.

– The apron of the Entered Apprentice is of white leather, rounded at the

bottom, with a pointed flap, worn raised. The Fellowcraft wears the same with

the flap turned down, and the Mason (Master) wears a white satin apron with a

curved flap, edged with crimson, and embroidered with a square and compass,

enclosing the letter G. The letters M and B, and three stars also appear. It is

lined with black silk and embroidered with the skull and crossbones and three

stars.

Switzerland.

– The clothing is simple. The Entered Apprentice apron is white with the lower

corners rounded. The Fellowcraft has blue edging and strings, and the Master

Mason has a wider border and three rosettes in the body of the apron, while the

flap is covered with blue silk. The apron of the Grand Officers is edged with

crimson, without tassels or rosettes, except in the case of the Grand Master,

which has three crimson rosettes.