John Pine, a celebrated engraver of the 18th century, remains an enigmatic figure overshadowed by his more flamboyant contemporary, William Hogarth. Pine’s contributions to the world of art, despite being less recognized, were significant and diverse, ranging from heraldry to the intricate illustrations that graced the pages of bestsellers like Daniel Defoe’s “Robinson Crusoe.”

A London native, Pine embarked on his artistic journey as an apprentice to a goldsmith, a role that laid the foundation for his eventual mastery in engraving. In 1718, he became a freeman of the city, marking the beginning of a career that would see him rise to become one of the most accomplished engravers of his generation. His work, though lacking Hogarth’s aggressive originality, was esteemed for its precision and adherence to classical and continental influences, showcasing a wide-ranging portfolio that included not only book illustrations but also heraldic art, maps, and facsimiles of historical documents.

Pine’s social life intertwined closely with Hogarth’s, with both men sharing a passion for the burgeoning social scene of London’s coffee houses, such as the famous Slaughter’s Coffee House in St Martin’s Lane. This era also saw them engaging in Freemasonry, a new social craze sweeping through London in the 1720s, further binding their connection.

Despite the vibrancy of Pine’s career and his contributions to copyright legislation aimed at protecting artists’ income, his friendship with Hogarth would cast a long-lasting shadow. Hogarth’s depiction of Pine as a fat friar lunging for beef in the painting “O, The Roast Beef of Old England” (or “The Gate of Calais”) not only mocked Pine but also cemented his nickname as ‘Friar Pine’ for life. This portrayal, stemming from Hogarth’s acerbic wit and Francophobe tendencies, became a source of guilt for Hogarth, who later painted an affectionate portrait of Pine in the style of Rembrandt as a gesture of reconciliation following Pine’s death.

Pine’s legacy, while less celebrated than Hogarth’s, embodies a blend of professional success and personal discretion. His work, though more traditional, contributed significantly to the art of engraving in 18th-century England, offering a counterpoint to Hogarth’s satirical and distinctly English style. The narrative of John Pine’s life and career, from his artistic achievements to his role in Hogarth’s infamous painting and their shared Freemason activities, paints a picture of a man whose influence and contributions to English art and society deserve recognition beyond the shadow of his more famous friend.

Pine was the model for the friar lusting after a joint of beef in the painting by his fellow freemason, William Hogarth, named, after a popular song of the period, O The Roast Beef of Old England or The Gate of Calais.

Library and Museum of Freemasonry

Senex probably knew of Pine through his business associate William Taylor, the publisher of Robinson Crusoe, but Pine was not an obvious choice for the job. Many other prestigious artists were also Freemasons, including the most celebrated artist of the time, Sir James Thornhill, as well as Joseph Highmore and Hogarth himself.

The frontispiece of the Book of Constitutions shows John, 2nd Duke of Montagu, Grand Master from 1721-1722, together with his Deputy and Wardens, handing the Constitutions to his successor, Phillip, Duke of Wharton, Grand Master 1722- 1723, who is also flanked by his Deputy and Wardens. Beneath the figures is the 47th Proposition of Euclid.

The Grand Officers are framed in a classical setting representing each of the orders of architecture, with the Sun God Apollo in his fiery chariot above. The design and handling of perspective is very striking. Underneath the picture are the words ‘Engraved by John Pine in Aldersgate Street London’, but the sophisticated treatment of the scene suggests it may have been designed by someone else, perhaps Thornhill, who designed an engraving of King Solomon with Hiram Abiff used in various Masonic publications from 1725.

It is not known when Pine became a Freemason. He was a member of the prestigious Lodge which met at the Horn Tavern in Westminster, one of the four Lodges which formed the Grand Lodge in 1717, now the Royal Somerset House and Inverness Lodge No. 4. He also belonged to the Lodge which met at the Globe in Moorgate, now Old Dundee Lodge No. 18. In 1730, Pine served as Marshal at the Grand Feast, directing proceedings ‘with his truncheon blew, tipt with gold’.

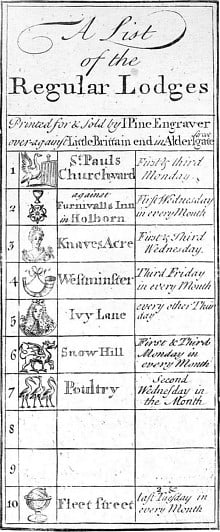

Following his success with the 1723 Book of Constitutions, Pine became the engraver preferred by Grand Lodge. From 1725 to 1741, he produced the annual engraved lists of Lodges. These were directories of Lodges warranted by Grand Lodge, giving details of their time and place of meeting. Each Lodge is distinguished by a miniature engraving of a sign appropriate to the Lodge, usually that of the tavern where the Lodge met. These tiny books are not only charming works of art, but also vital evidence for the early development of Freemasonry.

The Masonic engravings by Hogarth, such as the drunken Freemason returning home in ‘Night’, suggest a troubled relationship with Freemasonry. Pine was more willing to place his artistic gifts directly at the service of the Craft. He enthusiastically suggested ways in which he could assist Grand Lodge, by for example etching minutes of its meetings so that they could be quickly distributed. Pine’s relationship with Grand Lodge was important in his later development as an artist. Freemasonry apparently brought him in contact with the antiquary and scientist William Stukeley, and Pine engraved some of Stukeley’s drawings to illustrate his historical compilation Itinerararium Curiosum. Pine’s interest in wider philosophical issues is evident in his illustrations of Henry Pemberton’s 1728 View of Newton’s Philosophy, a popular account of Newton’s theories.

Pine not only illustrated this volume, but also subscribed to it, together with his fellow artists and Freemasons, Highmore and Thornhill. Thornhill’s patronage again proved important for Pine in 1725 when he obtained an important commission for both Highmore and Pine to produce illustrations of a procession of the Order of the Bath. As Pine worked increasingly closely with the European artists who gathered at Old Slaughter’s and elsewhere, he developed more ambitious projects. Particularly important was the influence of Hubert François Gravelot, who arrived in London to assist with the illustrations for a huge encyclopaedia of religious ceremonies begun by Bernard Picart. Pine collaborated with Gravelot on his most demanding undertaking to date, a series of engravings of 16th century tapestries in the House of Lords depicting the defeat of the Spanish Armada. These sumptuous works were described by Horace Walpole as ‘ornaments to a princely library’.

Between 1733 and 1737, Pine was engaged on his masterpiece, an edition of the works of Horace. Pine’s Horace is the greatest achievement of 18th-century book art. Each part of the hundreds of pages – from the elegant illustrations based on classical jewels to the text itself – was engraved by Pine himself. Such huge projects required lavish funding. In the 18th century, this was obtained by collecting advance subscriptions to the book, an activity in which Pine was a past master.

The subscription list to Pine’s Horace is a directory of London’s social and intellectual stars, from the Prince of Wales to Handel, Pope and Hogarth. Pine’s contact as a Freemason with aristocrats such as the Duke of Richmond and Lord Inchiquin, while they were Grand Masters, assisted in building up these lists. Pine’s entrepreneurial and artistic skills were vital in enabling the surveyor John Rocque to produce the first detailed street plan of London. Rocque’s scheme had foundered due to lack of support, but Pine obtained the backing of the Royal Society and the City Corporation, and again secured vital subscriptions.

Pine’s technical expertise as an engraver was essential in preparing the 24 huge sheets of the map, which finally appeared in 1747. Pine’s achievements brought office and honour. In 1743, he became Engraver of His Majesty’s Signet and Seals, and in the following year Bluemantle Pursuivant in the College of Arms. Hogarth’s depiction of him as ‘Friar Pine’ doubtless (perhaps deliberately) threatened this hard-won respectability. The prints of Hogarth containing references to Freemasonry have been minutely studied. Yet the works of Pine more effectively evoke the intellectual milieu of Freemasonry before 1750: the determination to recapture the ‘Augustan style’; the concern with antiquity; and the fascination with the new Newtonian science. Pine emerges as a man who embodies the spirit of early Freemasonry – intensely sociable but seeking in that sociability to explore the new horizons offered by the ‘century of enlightenment’.

Professor Andrew Prescott is Director of the Centre for Research into Freemasonry at the University of Sheffield