Tea and sympathy

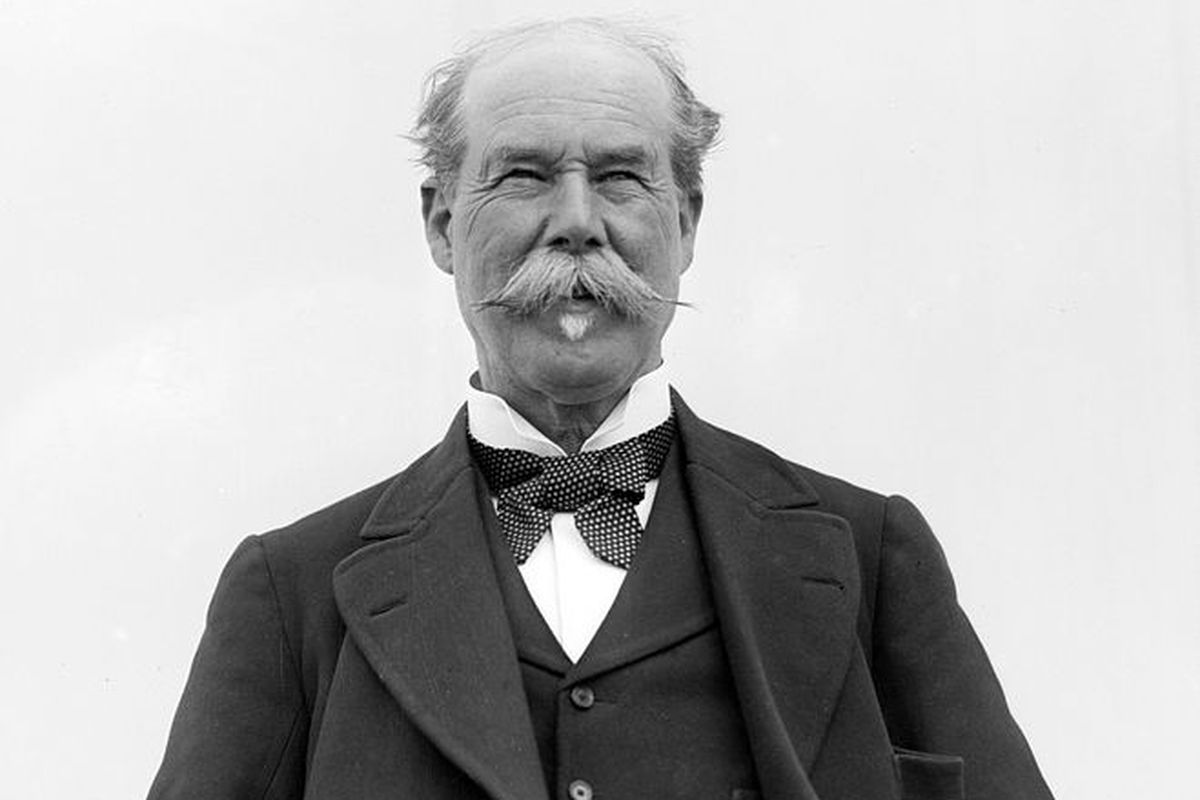

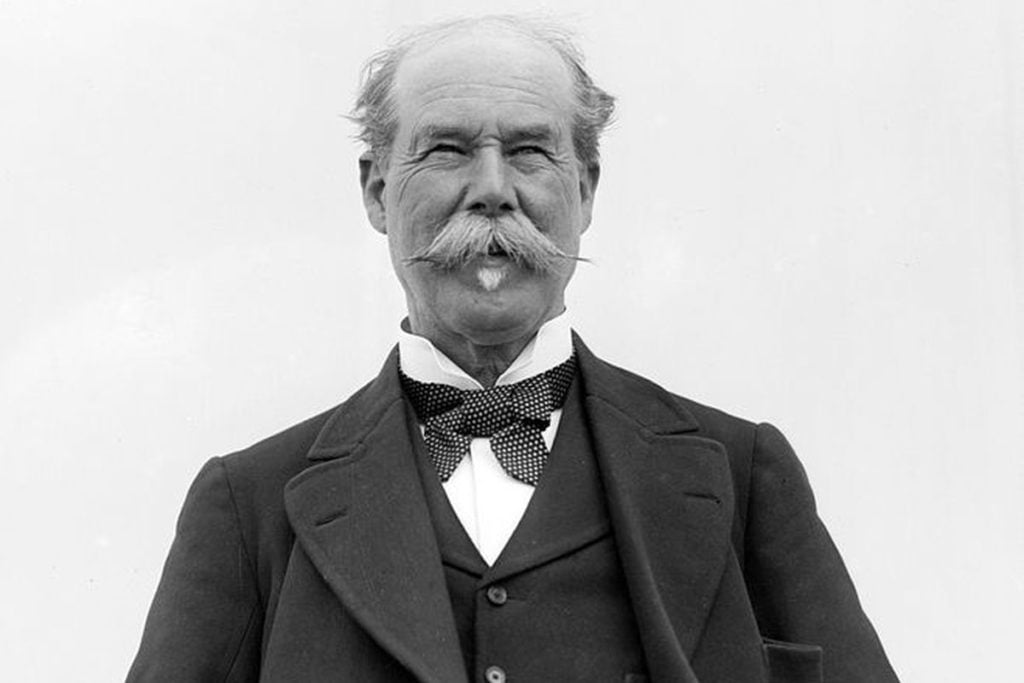

A self-made man who brought tea to the British masses, Freemason Sir Thomas Johnstone Lipton also campaigned for the sick and the poor, as Philippa Faulks discovers

Many masonic lodges around the world can boast of a famous member among their ranks, but Glasgow’s Lodge Scotia, No. 178, has one rather remarkable brother – Sir Thomas Johnstone Lipton. As with many other masons quietly carrying out acts of philanthropy, Lipton remains an unsung hero.

Lipton was a self-made man, endowed with the energy and drive to revolutionise the grocery trade and subsequently distribute large portions of his amassed fortune for the benefit of others.

Alec Waugh, in The Lipton Story, describes him as ‘a legend in his own lifetime, a millionaire before he was 40, an intimate of royalty and an unforgettable sportsman on both sides of the Atlantic’.

Born on 10 May 1850 into a respectable working-class family in Glasgow, Lipton was the youngest of five children. His parents had emigrated from Ireland to Scotland in the late 1840s due to the devastation of their smallholding in the Irish potato famine of 1845. By the 1860s, resilient to the core despite having also lost four of their children in infancy, the couple established a small shop selling butter, ham and eggs.

Young Lipton, now the only surviving child, received a good but basic education at St Andrew’s Parish School. However, wishing to help support his parents, he left school at 13 and worked his way through various uninspiring jobs until he signed up as cabin boy on a steamer between Glasgow and Belfast. He earned eight shillings a week and it was the start of a lifelong passion for travel and sailing.

According to A Full Cup, by Michael D’Antonio, Lipton stated that ‘it was good to be alive and better still to be a cabin boy on a gallant Clyde-built steamship’. The opportunity to go further than Belfast presented itself sooner rather than later when he was let go by the steamer company and, using his saved up wages, he booked passage to New York.

For five years Lipton travelled all over the country, employed in numerous and varied jobs, which included a stint at a tobacco plantation in Virginia. However, it was a job in New York as a grocery assistant and the subsequent initiation into the world of fast-paced advertising and retail competition that determined his decision to reverse his quest and find fortune back in Glasgow.

Back home he soon opened a shop of his own, which, with his acquired business acumen, expanded nationally and the Lipton empire was born. He saw an opportunity to branch out from ham, eggs and butter into the tea trade.

‘In 1898, he received a knighthood for his contribution to business and for his charitable work.’

A special blend

Without Lipton’s efforts, our great British passion for tea would never have been quite so widespread. In the mid-to-late 1800s, tea was still a precious – and expensive – commodity available only to the upper echelons of society. But as tea prices began to fall, Lipton saw a way of fulfilling a demand from the middle and lower classes. He decided to do away with the middleman and gradually acquired his own tea plantations in Ceylon.

Lipton improved the lives of the tea blenders and pickers with increased wages and created his own unique blends, which he shipped back to the UK to sell by the pound, half pound and quarter pound to ordinary folk. He improved on this by having the tea blends tailored to the area where the shops were located; his adverts then boasted that it was ‘the perfect tea to suit the water of your town’.

Lipton tea soon became a household name. After the death of his parents in 1898, he was persuaded to move his business to London and capitalise on its success – Lipton floated his company on the Stock Exchange for £2.5 million.

Perhaps more important than the introduction of our national beverage to all social classes was Lipton’s boundless altruism, social philanthropy and selfless actions during World War I. In 1898, he received a knighthood for his contribution to business and for his charitable work. During 1897, the Queen’s Diamond Jubilee year, he had donated £25,000 to the Princess of Wales to help set up a trust providing meals to the poor of London.

Being in London saw Lipton become friends with then Prince of Wales, Albert Edward, later to become Edward VII. The two men were matched in their passion for yachting – and also bonded thanks to their membership of Freemasonry.

The Prince of Wales became Patron of Scottish Freemasonry the same year that Lipton joined Lodge Scotia on his return from the United States in 1870. Initiated on 31 May, he was then both passed and raised on 17 August of the same year.

Lasting legacy

As a keen yachtsman, Lipton challenged five times for the America’s Cup between 1899 and 1930, although he never won a thing. However, in 1915, his yachts were put to use when a typhus epidemic broke out in Serbia during World War I.

Responding to a national call to action, Lipton put his yachts at the disposal of the Red Cross, the Scottish Women’s Hospitals Committee and the Serbian Relief Fund, for transporting medical volunteers, doctors, nurses and urgently needed medical supplies.

At the height of the epidemic, Lipton set sail in his steam yacht Erin to Serbia, on an expedition ‘sent out by the Joint Committee of the British Red Cross and the Order of St John’. The purpose was to report on the massive devastation wrought by the disease and to appeal to the world for humanitarian aid.

On his return, he made a lengthy appeal in The Times for funds and assistance, stating that: ‘Typhus… is spreading like a terrible blight from which neither man nor woman nor child of any station in life is immune.’ He was made an honorary citizen of the city of Niš in northern Serbia for his humanitarian service.

Sir ‘Tommy’ Lipton died in his sleep at his home in Osidge on 2 October 1931, at the age of 81. Unmarried and without heirs, his fortune was distributed among friends, servants and to establish dedicated foundations, but the majority of his estate was left in trust to Glasgow, his beloved city of birth. By 1946, all funds had been distributed; the Lipton trust had bestowed £821,000 to various good causes. Today, his commercial legacy lives on – his teas still resplendent in their famous yellow boxes.