Letter from Spandau

Correspondence sent over a hundred years ago reveals what life was like for masonic prisoners in Ruhleben camp. Director of the Library and Museum of Freemasonry Diane Clements opens the archive

On 18 December 1914 an extraordinary document arrived at Freemasons’ Hall in London addressed to Sir Edward Letchworth, the Grand Secretary. It began: ‘We, the undersigned brethren, at present interned with other British civilians at the concentration camp at Ruhleben, Spandau, Germany, send hearty good wishes to the Grand Master, officers and brethren in Great Britain, hoping that we may have the pleasure soon of greeting them personally.’

Among the ‘undersigned’ was Alexander Cordiner from South Shields, master of SS Heworth, a cargo ship berthed near Hamburg when war broke out in August 1914. He was just one of more than 10,000 British nationals living, working or on holiday in Germany who were interned by the German government as enemy aliens.

Many were taken to the Ruhleben camp at Spandau, west of Berlin. The camp was situated on a racecourse with barracks built in and around the stables to house the 4,000-5,000 internees. Ruhleben was run by the inmates who quickly established a church, library, sports and social clubs, a postal service and camp magazine.

The letter was written by Walter P Goodall of Lodge of Freedom, No. 77, Gravesend, and accompanied a list of more than a hundred Freemasons. On 13 February 1915, he sent a second letter with another forty-five names. Together, they detailed Freemasons who were members of lodges in England, Australia, Egypt, Hong Kong, Ireland, Scotland, South Africa, South America, the United States, the West Indies and even Germany.

In August 1915 another internee, Percy Hull, wrote to Grand Lodge to advise that there were now about two hundred Freemasons there, the majority receiving few if any food parcels. His letter helped to launch a campaign to support the internees. Alfred Robbins, President of the Board of General Purposes, welcomed the formation of what became known as the Ruhleben Fund, stating: ‘They are prisoners of war only in the sense of being detained during wartime; and their case is particularly hard because their businesses have been ruined and they and their families brought near to destitution.’

Parcels of support

The Fund enabled parcels to be sent every fortnight, which provided each masonic internee with three parcels over an eighteen-month period. Grand Lodge approached Sir Richard Burbidge, the managing director of Harrods, Knightsbridge, and parcels were sent to Percy Hull for distribution. One internee, S F Sheasby, reported in 1917 to the Old Masonians Gazette that they contained tea, coffee, cake, biscuits, potted meat and oats. By December 1917, more than £6,700 had been received for the Ruhleben Fund, the equivalent of about £250,000 today.

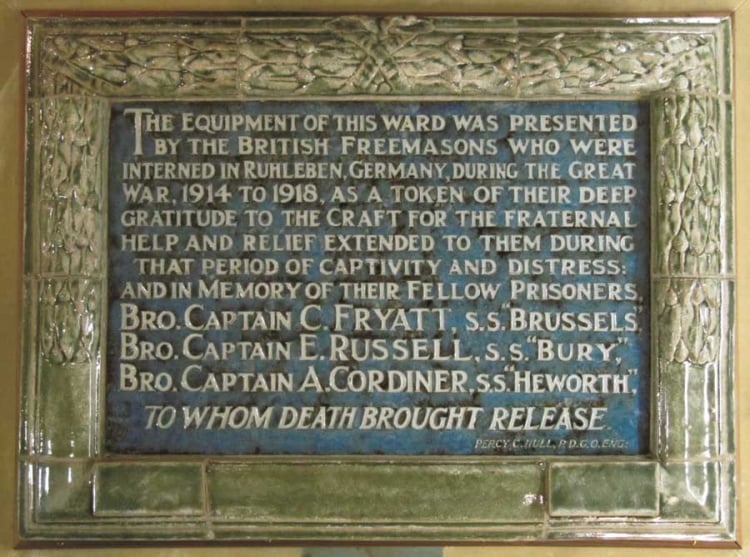

Three of the internees at Ruhleben are remembered on a large ceramic plaque, which was originally installed in the Royal Masonic Hospital and funded by the Ruhleben internees. Charles Fryatt of Star in the East Lodge, No. 650, Harwich, was a Merchant Navy captain who was briefly sent to Ruhleben in 1916 after his ferry, SS Brussels, was captured by German destroyers.

Fryatt had successfully defended two of his ships from German U-boat attacks a year earlier and had been rewarded for his actions with gold watches from both his employers, the Great Eastern Railway Company and The Admiralty. The latter watch was inscribed: ‘Presented by the Lords Commissioners of the Admiralty to Chas. Algernon Fryatt Master of the SS Brussels in recognition of the example set by that vessel when attacked by a German submarine on March 28th, 1915.’ This inscription was used as an excuse by the German authorities to try Fryatt at a court martial and subsequently execute him.

The second name is that of Edward Russell, a merchant seaman and member of the Earl of Yarborough Lodge, No. 2770, in Grimsby who died of natural causes in the camp in December 1917. The third name is that of Alexander Cordiner, the SS Heworth master and a member of St Hilda’s Lodge, No. 240, South Shields, who had been at Ruhleben since late 1914 and died there in March 1918. The plaque is now on display at the Library and Museum of Freemasonry in Freemasons’ Hall, Great Queen Street.

|

Letters to the Editor – No. 30 Summer 2015 Ruhleben remembered Sir, I was interested to read the article in the spring issue of Freemasonry Today about Ruhleben camp. My grandfather, John Clegg Fergusson, was a master dyer. He left Batley in the West Riding of Yorkshire with his wife and son, Alex, in the mid 1890s and settled in Germany where he was manager of the dye house in a textile mill, and was joined by his apprentice from Batley, Clifford Leach. On the outbreak of war, my grandfather and Clifford Leach were detained in Ruhleben camp as ‘guests of the Kaiser’ – enemy aliens. It was decided to allow my grandmother and her two younger children to travel home. My grandfather was eventually repatriated in 1916 but the story did not stop there. Clifford Leach, my father and his brother were all to become members of Trafalgar Lodge, No. 971, in Batley. Clifford Leach’s son, Harry, followed his father into the textile industry and when he was a member of a lodge in Manchester I visited him there, and he made the journey across the Pennines to visit my mother lodge in Morley. Harry’s death a few years ago brought an end to a friendship between the Leach family and the Fergussons that had lasted for over a century, a friendship in which both Ruhleben camp and Freemasonry played a part. James Fergusson, Lodge of Integrity, No. 380, Leeds, Yorkshire, West Riding Sir, I greatly enjoyed your article by Diane Clements, ‘Letter from Spandau’, in the spring issue. I wish that I had known it was to appear as I could have supplied a little more information. You may be interested to know that the Percy Hull mentioned went on to become Sir Percy, knighted for his efforts in resurrecting the Three Choirs Festival after World War II. During Hull’s internment, Dr George Robertson Sinclair (see ‘Elgar Connection’, p9 in the same issue), Grand Organist and Organist of Hereford Cathedral, died suddenly and Hull, at that time his assistant, was appointed in his place. Not only did Sir Percy follow Sinclair into the cathedral post, he also followed him as Grand Organist. I had the honour of conducting the cathedral choir at the dedication of his memorial in the cathedral as well as the Herefordshire Orchestral Society, in which Lady Hull played. Robert Green, Cantilupe Lodge, No. 4083, Hereford, Herefordshire Diane Clements, Director of The Library and Museum of Freemasonry, responds: Several people have mentioned Percy Hull’s later career. We have such limited space in Freemasonry Today that we are not able to develop articles as fully as possible but I appreciate all the information readers provide. |