On 19 July 1939, some 12,000 Freemasons were present at an Especial Grand Lodge at Olympia to witness the installation of the new Grand Master, the Duke of Kent, by a Past Grand Master, King George VI, who was also his brother.Representatives from many overseas countries were present: Australia, Canada, Finland, the USA, France, Norway, Greece, Denmark and the Netherlands.

On 19 July 1939, some 12,000 Freemasons were present at an Especial Grand Lodge at Olympia to witness the installation of the new Grand Master, the Duke of Kent, by a Past Grand Master, King George VI, who was also his brother.Representatives from many overseas countries were present: Australia, Canada, Finland, the USA, France, Norway, Greece, Denmark and the Netherlands.

By way of contrast, seven weeks later the Grand Secretary, Sydney White, reported to Russell McLaren, President of the Board of General Purposes, on the low numbers attending the Quarterly Communication of Grand Lodge held on 6th September:

“Grand Lodge on Wednesday with an attendance of about 20 was not a prolonged business. I think we started about eight minutes to six, as everyone who seemed likely to attend was then present, and we were out about 5 minutes past.”

On 1 September, the German army invaded Poland and on 3 September, Britain declared war. Grand Lodge had been unable to cancel its September meeting, but in a notice dated 1 September, urged members not to attend due to concerns about air raids and enemy attacks.

Within a year, as Germany took control of much of continental Europe, Freemasonry had been banned in many of the countries which had sent representatives to that July meeting.

Since the Czech crisis in September 1938, which had taken Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain to Munich to negotiate with Hitler, there had been a growing public perception in Britain that war was imminent. Rearmament in Britain had begun on a large scale in 1935 to counter Germany’s growing military strength in the air. After September 1938, precautions for the security of the civilian population were increased with the introduction of air raid precautions and the development of procedures for evacuation from large cities.

Although Freemasonry remained staunchly non-political, the build-up to war was echoed in the Masonic newspapers of the time, such as the Freemason’s Chronicle, which commented in October 1938 shortly after the Munich Agreement, that “the past days have created a state of tense anxiety by the swiftly gathering clouds of war”.

When war broke out, all Lodge and Chapter meetings were suspended. However, this was relaxed the following month, and meetings were resumed under “special directions”.

These included giving Masters (or Principals) the power to cancel any regular meeting, even if it had already been summoned, if circumstances appeared to warrant it, or to alter the day or place of a meeting. These special directions largely remained in force until December 1945.

Another of the special directions concerned proceedings after Lodge meetings, which were to be “brief and simple”. Food rationing was introduced in January 1940 and was not finally ended until 1954. Rationing for clothing was introduced in June 1941 and was only lifted in March 1949.

Both were to have an impact on Masonic meetings. In 1941, permission was given by Grand Lodge for gloves not to be worn during meetings as they were becoming difficult to obtain and all clothing needed coupons.

Administrative documents, such as the reports of the proceedings of the Quarterly Communication of Grand Lodge, were also reduced in length as paper became rationed.

The Library and Museum at Great Queen Street was temporarily closed in September 1939, but soon reopened, although the china and glass were stored in the basement, the pictures, aprons and furniture moved to a mezzanine floor and the silver and jewels were kept in the safe.

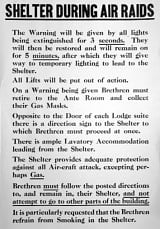

At the outbreak of war, the basement of Freemasons’ Hall was scheduled as an air-raid shelter to accommodate 2,500 people in the daytime and 1,000 people at night, although this number was often exceeded. Members of staff became volunteer shelter wardens.

The Grand Secretary took a great personal interest in the work, and during the latter part of 1940 he remained on the premises at night and took his turn in the shelter warden duties. Miss Haig, his secretary, and other female members of staff, were responsible for first aid and running the canteen.

Freemasons’ Hall was lucky to survive without any major damage during the bombing raids on London. During the Blitz, at 9.10pm on Saturday, 11 January 1941, bombs fell on the nearby premises of Lambert and Butler and on Peabody Buildings. The blast broke all the windows on the Wild Street side of the building and some on the Wild Court elevation.

The hall was converted into a temporary first aid post for the injured and homeless. Many other Masonic buildings were damaged or destroyed by bombs, including the Bristol Masonic Hall and Hope Street in Liverpool. Other Masonic meeting places, such as livery company halls in the City of London, and restaurants, were damaged and many Lodge records and items of furniture were destroyed.

The UK mainland never suffered Nazi occupation, but in 1940 the Germans occupied the Channel Islands. Against this background, and with the fall of France in June 1940 and the Blitz continuing, measures were taken to preserve some of the most important original Grand Lodge records.

In October 1940, the Grand Secretary wrote to his opposite number in New South Wales, New Zealand, Massachusetts and Canada:

“Dear Brother Grand Secretary,

We have considered it desirable to place certain of our original documents in a place of safety in order to preserve them for posterity. Should misfortune befall all who are aware of the location, it is desired that the information be made available to their successors.

It has been decided that a sealed envelope, which is enclosed, be deposited with four Grand Lodges, of which yours is one, asking them to preserve it and return, unopened, upon receipt of a letter making the request, or a cable worded ‘Return Envelope’.

I feel sure that you will not mind doing this service for us.”

The Grand Secretary of Canada in Ontario replied:

“We gladly accept the trust and assure you that your instructions will be strictly carried out. Let us hope, however, that we will soon receive an “all clear” cable and that victory will be ours.”

When return of the envelopes was requested on 10 October 1945, the Grand Secretary wrote:

“In those days we were very concerned as to the safety of many of our historical records and it was a comfort to know that certain papers were deposited with you.”

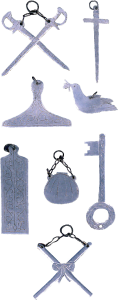

In the summer of 1940, Grand Lodge began a scheme of collecting together Masonic jewels donated by members, which were then melted down for the war effort. Over £10,000 was raised by November 1940. A further cheque for £2,500 in December 1942 was acknowledged in writing by Sir Kingsley Wood, the Chancellor of the Exchequer, himself a Freemason.

Masonic charities replaced their metal steward’s jewels with card or plastic versions, which were in some cases replaced by a metal version once the wartime restrictions were lifted. Pupils at the Masonic schools donated the money that would have bought their school prizes to charity. Threequarters of the beds at the Royal Masonic Hospital were set aside for the treatment of the armed forces, and by the end of the war over 8,600 had been treated there. Masonic charitable donations were also made to other organisations, including the Red Cross and the St. John’s War Fund.

However, Freemasonry continued during the war – Grand Lodge continued to meet, by and large Lodge and Chapter meetings continued and new Lodges were established – over 350 being formed between 1943 and 1945.

Some of these Lodges were founded as a Masonic home for those involved in the war effort.

For example, Sword and Trowel Lodge No. 5847 was formed in 1942 by members of the 54th (Surrey) Battalion of the Home Guard – the Local Defence Volunteers – which was formed early in 1940, and by that summer over one million men had joined. The Venture Adventure Lodge No. 6022 was formed in 1944 for those connected with the Air Training Corps.

At the beginning of the war, the Grand Master had taken up an attachment to the intelligence division of the Admiralty with the rank of Captain (later Rear-Admiral). In April 1940 he transferred to the Royal Air Force, renouncing his honorary rank of Air Vice-Marshal on the grounds that it would make him senior to many men of greater experience. He was appointed Group Captain in the Training Command and was given responsibility for supervising welfare work at the larger air force stations, a job that involved considerable travel within the country and overseas.

On 25 August 1942, shortly after being promoted Air Commodore, he set out to inspect the RAF establishments in Iceland. His plane crashed at the Eagle’s Rock, near Dunbeath in Caithness, and all on board were killed. The Acting Grand Master, the Earl of Harewood, at the September meeting of Grand Lodge, reported this tragic news.

By the outbreak of war, Britain had already become a safe haven for Jewish and other refugees from Europe, especially Germany. As the war progressed, troops from other countries – Poland, Czechoslovakia and France – based themselves in Britain.

They were joined by soldiers from Commonwealth countries, and American troops also arrived following the entry of the US into the war. Grand Lodge faced a number of challenges in dealing with this situation. The first that needed to be tackled by late 1939 was the position of brethren of enemy nationality or birth who were members of English Lodges. In the 1914–1918 War, it had been decided that brethren of enemy birth should not attend any Masonic meeting while the war continued. This policy seems to have been readily accepted by both Lodges and the brethren affected.

However, in 1939, the situation was complicated by the issue of refugees. The Board of General Purposes put forward a two-part proposal – the first part mirrored the policy of the earlier war, seeking voluntary withdrawal. The second part proposed that brethren of enemy birth might be requested by the Master of the Lodge to abstain from attending if the Master was of the opinion that “the presence of such brother would create discord.”

The Freemason’s Chronicle pointed out that the use of the term ‘enemy birth’ rather than ‘enemy nationality’ was harsh and did not allow for the process of naturalisation, and that by putting the onus on the Master of the Lodge, the policy was liable to be inconsistently applied.

This issue caused considerable debate and was amended to read: “No Brother being a national of any state with which Great Britain is at war shall attend or be admitted to any Masonic Meeting held under the English Constitution.”

Many Czech Freemasons fled to London, where they established the Czech Grand Lodge-in-Exile. This consecrated a new Lodge, Comenius-in-Exile, which met at the Café Royal from 1942 until its return to Prague in 1947. Other foreign troops visited or joined English Lodges. As early as August 1940, New Zealand Lodge No 5175 included 80 members of the New Zealand armed forces among its membership.

During the later stages of the war, after the Allied landings in Italy and following D-Day in June 1944, Freemasons started to form Masonic clubs or societies in towns across Europe where they were stationed. The clubs were informal, unofficial gatherings, but were not discouraged by the members’ Grand Lodges, as they embodied the principle of fraternity. Membership of the clubs was often short-lived, reflecting the fact that they were run by men on active service.

As the clubs were informal Masonic gatherings, no ritual was performed or members initiated. Time was spent discussing Freemasonry, listening to lectures and raising money for local and Masonic charities. Two examples were the Friday Night Club for Freemasons stationed in Cairo, and the Tyre-Rhenian Masonic Club in Italy.

Other ‘Masonic’ meetings (usually Lodges of Instruction) were held in prisoner-of-war camps in Europe and the Far East, and the working tools and archives of these meetings remain poignant reminders of Freemasonry under duress.

The war in Europe ended on 8 May 1945. Fighting continued in the Far East until August, and wartime conditions

persisted for even longer – food rationing continued until 1954, with Grand Lodge proceedings in September 1946 and afterwards recording the “many offers of gifts of food parcels… received from different parts of the world”.

Clothes rationing ended in 1949 and Grand Lodge hoped that “dark suits, black shoes and ties, and white collars will become the general wear in Masonic clothing”. The wearing of white gloves continued to be left to the discretion of the Master.

After the war, Lodges were asked to document their wartime experiences and list members who had served or been killed, with the view to producing a Book of Remembrance to mirror that produced after the 1914-18 war. However, only about half the Lodges replied, and this material was later used as the basis for an incomplete Roll of Honour produced by Keith Flynn.

When the United Grand Lodge of England met for its regular quarterly meeting on 6 June 1945, a month after the end of the war in Europe, tribute was paid to the Masonic Lodges which had continued to carry out their duties in spite of the difficulties and dangers of the war. “Freemasonry has meant much to its members during the past five and a half years” said George Emmerson, the President of the Board, “it is hoped that the spirit which has sustained them will be maintained”.

Further Reading

Many Lodge histories include fascinating references to the wartime experiences of the members. Keith Flynn,Freemasons at War, 1991 Keith Flynn, Behind the Wire: an account of Masonic activity by prisoners of war, 1998