Dr Thomas John Barnardo (1845–1905), nicknamed ‘The Doctor’, was a leading reformer of the 19th century on a par with Sir Robert Peel, Elizabeth Fry and Florence Nightingale. Single-handed, over a period of four decades, he improved the life of hundreds of thousands of destitute children. His first home opened in the East End of London in 1870. At his death, in September 1905, there were nearly 8,000 children in 96 of his residential homes. Some 1,300 had disabilities and 4,000 were ‘boarded out’, namely placed with foster parents. An additional 18,000 children, controversially, had been sent to Canada and Australia.

Relatively late in his busy philanthropic career, in November 1889, Thomas Barnardo became a Freemason in London at the mature age of 44, being initiated into Shadwell Clerke Lodge No. 1910 at the Hotel Cecil in the Strand. The Lodge, warranted on 22 April 1881, was founded in November 1882 in honour of Colonel Shadwell H. Clerke, who had been appointed Grand Secretary of the United Grand Lodge of England two and half years earlier.

Barnardo’s progress through the three Degrees took place in the old-fashioned way: one degree a year. He was passed on 23 June 1890 and raised on 8 October 1891. Barnardo did not take office, although he continued his full membership to his dying day.

It is interesting to speculate as to what may have induced him to become a Freemason. In his youth he had been an avid reader of Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712–1778), the positive Swiss-born French [only from 1741 onwards, before moving to Luxembourg in 1757, fleeing to Switzerland in 1762 and then to England and back to Paris in 1767, but died insane] philosopher and writer and of Thomas Paine (1737–1809), the English intellectual, political and religious thinker.

Both men, although not Freemasons, advocated philosophies with which Masonic thinking, fashionable in the 1880s, not least because of Royal patronage, would be in sympathy. Indeed, Thomas Paine published his own theory on the origins of Freemasonry, which today remains only of interest as an historical curiosity.

More importantly, however, a greater influence on Barnardo to become a Freemason may have emanated from his friendship with Sir Henry Solomon Wellcome (1853–1936) the American-born British pharmaceutical entrepreneur. Here was a dedicated and very active Freemason, whose closeness to Barnardo was, at a later stage, greatly enhanced when, in 1901, Wellcome married Gwendolin Maud Syrie, Barnardo’s daughter.

Curiously, Henry Wellcome’s excessive Masonic activities, inter alia, were cited by his wife as to the cause of the separation between the two, which ended in a divorce in 1915, with W. Somerset Maugham being named as a co-respondent…but that is another story!

The Lodge records show that at a Lodge of Emergency held on 6 September 1889 at the Masonic Hall, Red Lion Square, London, Thomas John Barnardo, Esq, MRCS, aged forty [sic] was proposed by the Lodge Secretary, W Bro C.F. Matier and seconded by the Senior Warden, Bro W.C. Gilles. Bro Matier later became Grand Secretary of the Grand Lodge of Mark Master Masons (1889–1914) as well as Great Vice-Chancellor in the Great Priory of Knights Templar (1896–1914). Barnardo was balloted for and elected.

At the same meeting, Douglas Heron Marrable was also elected. Rather unusually, the Initiation, which took place at the next meeting on 25 November 1889, was an Installation meeting. RW Bro Major-General Lord John Henry Taylour PJGW (1831–1890), was in the Chair as Master and immediately following the Initiation ceremony, Barnardo’s seconder, Bro William Charles Gilles, was installed as Master.

The visitors included VW Bro Colonel Shadwell H. Clerke himself, RW Bro The Rt Hon the Earl of Euston, Provincial Grand Master of Northamptonshire and Huntingdonshire, RW Bro General I.W. Laurie, District Grand Master of Nova Scotia, Canada, VW Bro Frederick Adolphus Philbrick QC, Grand Registrar and Great Chancellor of Knights Templar and 32° in the Ancient & Accepted Rite and a well-known philatelist, among others. There is no record of Douglas Marrable, who had been elected with Barnardo.

At this meeting it was decided that the Lodge would move from the Masonic Hall, Red Lion Square to Mark Masons’ Hall at Great Queen Street, where the next regular meeting was held on 23 June 1890. It was W Bro William Charles Gilles’s first meeting in the Chair and a busy one – with five candidates for the Fellowcraft Degree. Bro Barnardo was passed to the Second Degree together with the following additional Brethren: Bros H.F. Matthews, J.L. Grossmith and Bros Newton, South and Savory, who were Passed at the request of the Master of the Grafton Lodge No. 2347.

Barnardo’s Raising coincided with a tragic event, the death of the newly elected Master of the Lodge, W Bro James MacDonald, who was killed on a railway line on 15 August 1891. A Lodge of Emergency was held on 8 October 1891 at Mark Masons’ Hall and Bro Barnardo was raised to the sublime degree of a Master Mason by the Immediate Past Master, W Bro W.C. Gilles, together with Bros Pirie, Cummins and Fullilove.

The only other mention of Bro Thomas Barnardo in the Lodge records is a resolution recorded for 25 September 1905 in which: The W.M. proposed and W Bro H.F. Matthews seconded that a letter of condolence and sympathy be sent to Mrs Barnardo on the loss of her husband, our Brother Dr. Barnardo. This was unanimously agreed.’

Tom Barnardo was born in Dublin, the son of a furrier. Little detail of his unhappy childhood has emerged. His reports from St. Patrick’s Cathedral Grammar School in Dublin show him to have been rebellious and an agitator, easily bored by lessons, and whilst talented with eloquence, he appears to have been confrontational and argumentative.

He was unsuccessful with his public school exams and, at 16, chose to cease his studies in favour of a short-lived apprenticeship to a wine merchant. A year later, in May 1862, Barnardo converted to become an Evangelical Christian and took to his newly acquired persuasion with zest and passion. He became impatient to convert others, teaching Bible classes in a Dublin ragged school and getting involved in home visiting.

His membership, with his whole immediate family, of the Plymouth Brethren, a Christian Evangelical religious movement, was to change his life. The movement, begun in Dublin in the 1820s by a group of prominent Christians, included Dr Edward Cronin, a pioneer of homoeopathy, Dr Edward Wilson, George Müller, founder of the Bristol Orphanage, and Anthony Norris, missionary to Baghdad and India, among others.

They felt that the Established Church had become too involved with the secular state and had abandoned many of the basic truths of Christianity. The movement spread rapidly and in 1831, by which time the membership had swelled to some 1,500, they met in Plymouth, England soon to be nicknamed the ‘Plymouth Brethren’.

Barnardo’s experiences in the ragged school, his continued preaching and teaching and his exposure to other philanthropists, James Hudson Taylor (1832–1905), the British Protestant Christian missionary, in particular, led him to choose a medical missionary career in China. With the help of his Dublin friends, Barnardo gained introductions and registered as a medical student in the prestigious London Hospital, now the Royal London Hospital, adjoining Whitechapel Road, in 1866.

Again, there is little information of his early years in London. He found residence in Stepney, close to the hospital, where he continued with his religious activities at the expense of his studies. In his first year as a medical student, in November 1867, he held the first of his many fund-raising meetings, the success of which enabled him to set up his own ragged school – The East End Juvenile Mission.

Famously, a young boy in the mission by the name of Jim Jarvis took Barnardo around the squalor and devastation of the East End. The images of children sleeping in the gutter and on rooftops so impressed Barnardo, that he decided to forgo his plans of work in China and dedicated himself to the destitute children of London. He walked the streets of the slum district and brought back to the mission destitute boys.

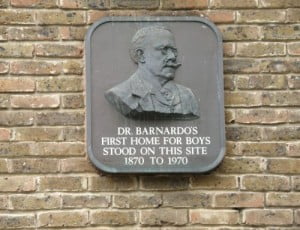

Within three years he opened the initial home for boys at 18 Stepney Causeway in 1870. The first 33 inhabitants were all older youths. Some could afford to pay, others were given work in the home whilst being taught how to fit into society. All the boys were treated equally, they were fed and clothed and prepared to face better lives.

In 1872, the year of the publication of his well-received book How It All Happened, he married Sara Louise (Syrie) Elmslie. A year later, with her enthusiastic assistance, he established the first home for girls, which opened at Mossford Lodge in 1873. It reached a peak in 1883 with the Village Home for Girls in Ilford, Essex, which was a complete community with 70 cottages, its own school, laundry, church and a population of over 1,000 children.

Meanwhile, his medical studies and status in the hospital suffered at the expense of all these extra-curricular activities. Fellow students complained of his religious enthusiasm and it took Barnardo almost a decade to take up and continue his medical career. A letter he wrote to the Justus Liebig-Universität Gießen, the University of Giessen, Germany in 1875, now in the archives of Barnardo’s in Barkingside, Essex, is both revealing and self-explanatory:

I became a medical student at the London Hospital in 1867 and entered Durham University the previous September and registered as a medical student in June 1868. I duly attended all hospital practice, medical and surgical for four years. In July 1869 I passed the first professional examination in anatomy and physiology at the Royal College of Surgeons, England, and hope to go up for the final examination in April next. The reason why I have not proceeded to qualify fully before this is that in 1870 I abandoned the study of medicine and took up the philanthropic work of rescuing destitute children from the streets of our great cities, much of the same character as your own celebrated Dr. Wichern of Hamburg.

Although I did not proceed with my studies I am generally called Dr. Barnardo and enclose my card … (I) shall be glad to know if you can allow me to be examined by your University early in December … Kindly let me know the subjects of examination. I can give testimonials of my professional knowledge etc., by respectable English medical men, if you will kindly tell me what you require, and I enclose in proof of the truth of my first statements two certificates of registration, which please return when you reply. Also state the amount of fees required…

Nothing appears to have resulted from this appeal and Barnardo continued his studies and obtained his diploma in April 1876 as a Licentiate of the Royal College of Surgeons. He returned to London and registered as a medical practitioner and exactly three years later, on 16 April 1879, he was elected a Fellow of the Royal College of Surgeons of Edinburgh.

He now dedicated himself with full vigour to the establishment of his homes and training schemes. He had initially rented canal-side warehouses and converted them to schools, later acquiring numerous properties in East London. He established an Evangelical mission church, set up facilities and provided for the disabled and those with special needs.

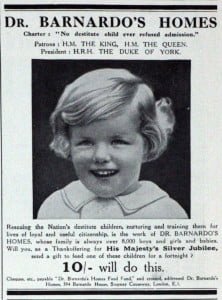

His commitments had become such that he needed ever more innovative methods to raise funds, often overrunning available resources. Here is where his particular expertise came into play. His great success relied on his capacity to organise mass charity events and raise funds for his projects. Much of the money for his schemes came, in small amounts, from a large number of donors, including children. They were encouraged to give through an organisation he founded in 1891 called The Young Helpers’ League.

At the time of Barnardo’s death, nearly 15 years later, the membership of the enterprise had grown to 34,000. Barnardo knew how to present his schemes and plans and gained important support in doing so.

A powerful and persuasive orator, he had already gained the support of Lord Shaftesbury (1801–1885) and of the banker, Robert Barclay (1843–1921). Shaftesbury Avenue, in the West End of London, was completed in 1886, and named in his memory. While using the course of existing streets, it demolished some of the worst slums, which Lord Shaftsbury had campaigned to eliminate from the area.

Thomas Barnardo was a controversial character by any standards. Some dispute his right to have used the term ‘Doctor’. He tended to ignore the various bodies and councils who set financial budgets and limits on the number of children to be cared for or ‘boarded out’. Boarding out was a fostering scheme started in 1887 when 330 boys aged between five and nine were sent to ‘good country homes’ far from the slums and parishes in which they had lived. In 1893 there were more than 2,000 children boarded out.

Barnardo was criticised for his lack of regard for what parents and the children themselves thought. He was an autocrat and imposed his thinking upon others. Another scheme, which was criticised and even resisted, was his plan to ‘board out’ illegitimate babies with their mothers, who were encouraged to go into service with an approved employer. Many charities refused to offer help to such mothers as it was seen as rewarding immorality.

A very important scheme of great concern and much criticised was that of child migration. Between 1882 and 1939 the agency sent over 30,000 children to Canada. The attitude of the agencies sending children to Canada, Australia and other countries was that they were providing them with a new start as they had no prospects in Britain and their families were seen as failing to provide adequate care for them.

Arguments were put forward that Dr Barnardo was the most influential figure in the child migration of the last half of the 19th century and he was accused of ‘spiriting’ children away to Canada against the wishes of their parents. This was emphasised by a number of court battles. Several more accusations were directed at Barnardo, many with no justification whatever: that the homes were badly managed; that the boys were cruelly treated; that there was no religious or moral training and that published photographs were falsified and intended to deceive the public.

Barnardo was also personally attacked and charged with improperly appropriating funds for his own benefit. At one stage Barnardo decided to go to arbitration under an Order of Court. In October 1877, the Arbitrators vindicated Barnardo, stating that there was no evidence to support any of the charges laid against him.

Thomas Barnardo was a great and charismatic philanthropist. He believed in what he did. He had huge abilities, especially to network and to present his work in a way that opened purse strings. He was a hard worker, with infinite projects and plans. And most importantly, he was exceedingly successful. It was inevitable that he would provoke gossip, speculation and even antagonism. His lifestyle took its toll and by the age of fifty Barnardo had some heart complaint. He ignored doctor’s orders to take a period of absolute rest and died on 19 September 1905 having spent a busy day and settled in an easy chair by the fireside.

The good he did lives after him.

Postscript

Barnardo’s stopped running homes for orphans over 40 years ago, but the work today is based on the same set of values on which the charity was first founded. Since 1867 the services provided have changed and they will continue to do so in order to meet the needs of children and young people of today. However, the aim of helping children and young people in the greatest need, stays the same.

Selected biography and acknowledgements

Barnardo’s on-line: http://www.barnardos.org.uk/ http://www.gracesguide.co.uk/and http://infed.org/mobi/

David Foster, secretary, Shadwell Clerke Lodge No. 1910, for special efforts.

John Hart, long-standing friend and mentor.

Bruce Hogg, for able and professional advice and proof-reading.

Hitchman, J. They Carried the Sword. The Barnardo story, Gollancz, London (1966).

Wymer, Norman. Father of Nobody’s Children, Longmans, London (1962)